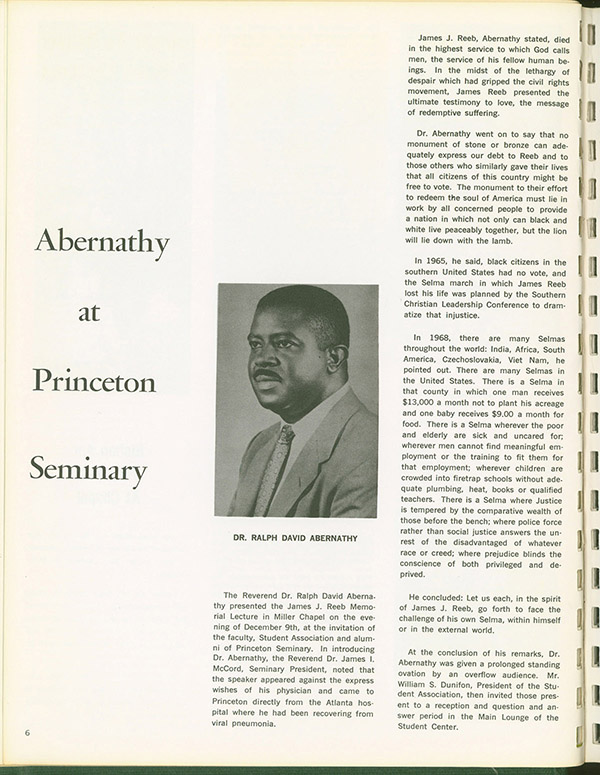

Ralph Abernathy delivered the fourth James Reeb Memorial Lecture (audio recording also available) December 9, 1968, eight months after his close friend and colleague, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. King’s “spiritual right-hand man,” and chief aide, Abernathy had taken King’s place as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The nation was reeling from demonstrations and backlash.

“If you have a sense of despair tonight about the possibility of meaningful reform in America and the prospects for a decent world society, I ask you to think of James Reeb. There was despair in 1965, too, but the undeniable urgency of the right to vote was so compelling that people went to Selma regardless of the risk and the odds against victory.”

Ralph David Abernathy was born tenth of twelve children in Linden, Alabama, March 11, 1926. His parents were sharecroppers who rose to own a five hundred-acre farm. Abernathy’s father was deacon in a local church, and the younger Abernathy considered the ministry from an early age. After military service at the end of World War II, he returned to Alabama and was ordained a Baptist minister in 1948. He received a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Alabama State University in 1950. His career in political activism began in college where he led demonstrations to protest poor campus living conditions. He earned a master’s degree in sociology from Atlanta University in 1951. He married Juanita Odessa Jones and they had three children.

Abernathy became pastor of the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1951. When Martin Luther King Jr. became pastor of neighboring Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, in 1954, the two men began a friendship and collaboration that continued until King’s assassination. They helped found the Montgomery Improvement Association, which grew out of the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-1956. King and Abernathy played key roles in the boycott, and Abernathy succeeded King as president of the MIA.

The MIA evolved into the SCLC, founded in 1957 by Abernathy, King and others to promote nonviolent activism. King was the organization’s first president, and Abernathy secretary-treasurer, later vice president. SCLC headquarters moved to Atlanta in 1960, where Abernathy became pastor of the West Hunter Street Baptist Church. He continued with the SCLC, leading sit-ins, marches, and nonviolent rallies throughout the South. In 1957 Abernathy’s home and the church were firebombed. His family survived unharmed, but the church was destroyed. Throughout the civil rights struggles, King and Abernathy were jailed together seventeen times.

Abernathy helped to mobilize the Freedom Rides in 1961, the Birmingham campaign of 1963, and the marches from Selma in 1965. He was with King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when King was shot in the head. Connect to audio of the Abernathy lecture:

After King’s assassination in April 1968, Abernathy became president of the SCLC and continued the Poor People’s Campaign, King’s last project, to call attention to national poverty. That May, near the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., fifty thousand poor and homeless people built a shantytown and stayed until police forcibly dismantled it one month later. Abernathy was jailed for unlawful assembly for twenty days.

He left the SCLC in 1977 and ran unsuccessfully for Andrew Young’s congressional seat. He then founded the Foundation for Economic Enterprises Development and served as pastor at the West Hunter Street Baptist Church until 1990. He received numerous awards and honorary degrees.

Abernathy faced criticism from other activists in 1980 when he endorsed Republican Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign and again with the 1989 publishing of his autobiography, which contained references to King’s personal life. He died the following year at the age of 64 of a heart attack.

Holmes writes of King and Abernathy’s rhetorical gifts to “capture the devout yet critical patriotism integral to the civil rights movement,” and of their “undying love for the principles of democracy and unyielding insistence that those principles be truly applied to all.” Miller Chapel was filled beyond capacity for Abernathy’s Reeb lecture, which received a prolonged standing ovation.

“We must go on, whether it be on marches and demonstrations and jailings, or in local community work. The only thing that can stop us is our own paralysis of will. I challenge you tonight to break out of that paralysis. I challenge you to join me in creating another Selma, in defying the ominous clouds of confusion and the fainthearted counsel of despair.”