Roy Wilkins gave the second James Reeb Memorial Lecture (Part 1, Part 2), “Life Given: For Freedom and For Love,” March 3, 1967, almost 50 years ago. His message of perseverance could have been delivered today.

“We prayed that the senseless killing of this good man would make the battle of Selma the last battle for freedom, but even as we prayed we remembered how many, down through the ages, had died for man’s forward inching and we knew in our hearts that after Reeb there would be more, many more, before the kingdom came.”

Roy Wilkins was born August 30, 1901, in St. Louis, the son of William DeWitte Wilkins, a minister, and Mayfield Edmundson. His parents were from Holly Springs, Mississippi, but fled when racial violence threatened his father. After his mother died in 1907, Wilkins, his sister and brother lived with their aunt and uncle, a sleeping-car porter, in a low-income integrated neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota. Growing up, Roy Wilkins had many white classmates, neighbors, and friends.

Wilkins studied sociology at the University of Minnesota where he supported himself working as a redcap, a dining-car waiter, and a slaughterhouse laborer. He also studied journalism, and was the only African American staff member of the campus newspaper, the Minnesota Daily. He was also editor of the St. Paul Appeal, an African-American newspaper. After graduating in 1923, Wilkins worked at the Northwestern Bulletin and became news editor of the Kansas City Call, a black weekly. He and social worker Aminda Badeau married in 1929. Living in Kansas City, Wilkins acutely experienced disparities between white and black neighborhoods and joined the civil rights movement.

In 1931 Walter White was executive secretary of the NAACP, the nation’s oldest and largest grassroots civil rights organization. He recruited Wilkins to be assistant secretary, beginning a 24-year apprenticeship between the two men. In 1934, Wilkins followed W. E. B. Du Bois as editor of Crisis, the organization’s official magazine. During the 1940s, the NAACP and Wilkins played a key role in national struggles against job discrimination, racial violence, and segregation in the armed forces. Fair employment practices became a high priority, and he chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, which in 1950 organized a mass rally in Washington.

That mobilization led to Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Arnold Aronson of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council founding the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a powerful civil rights lobbying coalition. A driving force in the organization, Wilkins successfully pushed major civil rights bills through Congress in the 1950s and 1960s.

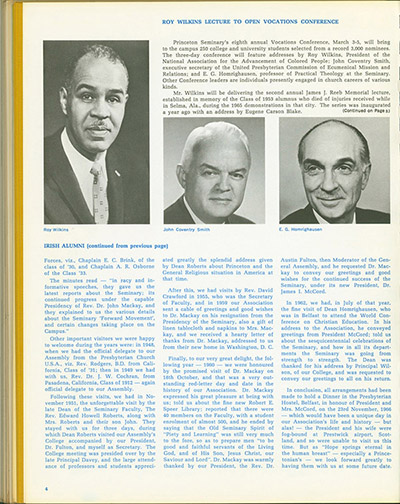

In 1955 after White died, Wilkins became executive secretary (later executive director) of the NAACP. Under his early leadership, the organization saw one of its greatest achievements, the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. He and NAACP lobbyist Clarence Mitchell worked with President Lyndon B. Johnson to secure passage of the civil rights acts of 1964, 1965, and 1968. In 1967, the year of his Reeb lecture, Wilkins was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Johnson.

A savvy advocate and negotiator, Wilkins sought reform legislatively, testifying before Congress and meeting with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter. His approach is remembered as being more careful than other early African American civil rights leaders. In her biography of him, Yvonne Ryan writes that Wilkins was “more comfortable walking the corridors of power than demonstrating on sidewalks.” He sought change via nonviolent legislative means rather than militant demonstrations. That said, he was a visible and active leader in key civil rights moments, including the 1963 March on Washington, the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965, and the 1966 March Against Fear. During his later years at the NAACP he faced challenges within the organization from younger activists promoting more radical methods and externally amidst the conservative eras of the Nixon and Ford presidential administrations.

He retired from the NAACP in 1977 at age 76 after 46 years and was succeeded by Benjamin Hooks. Roy Wilkins died in New York City in 1981. The Roy Wilkins Centre for Human Relations and Human Justice was established in the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs in 1992.

Box58_Wilkins_MSS_LOCLike other Reeb lecturers, Wilkins placed the tragedy of Reeb’s death within the context of the larger fight for freedom. He spoke at Princeton four days after the car bombing death of Wharlest Jackson, a married factory worker, father and treasurer of the Natchez NAACP. Jackson died after working overtime when his pickup truck was bombed in an attempt to kill him and George Metcalfe, a former Natchez NAACP president and voter registration organizer. Of the bombing, Wilkins said,

“What a fiendish and dastardly and cowardly obstruction to the unending crusade for freedom! And how futile! The march to the voting booths in Selma was not stopped by the brutal murderers of James Reeb and the march to better jobs, better families and better education for children in Natchez will not be stopped by the ghastly murder of Wharlest Jackson and the cruel maiming of George Metcalfe.”