Just as the civil rights movement encompasses more than one night in Selma, so does James Reeb’s faith journey extend beyond any one moment. Both narratives are complex, bound in personal struggles, historical realities, and societal change.

James Joseph Reeb was born in Wichita, Kansas, New Years Day 1927. His mother was Roman Catholic and his father German Lutheran. The family moved to Casper, Wyoming, where Harry Reeb worked in manufacturing and James attended high school. After graduating, he served in the US Army from 1945 to 1946 and attended St. Olaf College, graduating in 1950. While in college, he participated in the Missionary Study Group. He married Marie Deason and they had four children.

The GI Bill enabled James Reeb to attend graduate school, and he applied to Princeton Theological Seminary. In his application he wrote:

Just before leaving high school I made my decision to enter the ministry and was taken under care of Presbytery. Since that time I have never been without the conviction that I must carry the news of salvation to men.

Reeb’s biographer and employer Duncan Howlett wrote that Reeb experienced a theological awakening in his time at Princeton Seminary. During the spring term of his first year he visited the East Harlem Protestant Parish as part of a course on city churches. The trip to New York exposed him to urban poverty and racial disparities and the church’s efforts to combat them. He grew restless at Princeton. Earlier fundamentalist views from home and college were shaken and he began to have doubts about personal beliefs and denominational tenets.

A successful college student, he was frustrated in seminary classes and did average work despite assurances from advisors that religious doubt was common among seminary middlers. During his second year he began fieldwork at the Philadelphia General Hospital chaplaincy program and was increasingly drawn to community ministries and psychiatry. After graduation from Princeton in 1953 he was ordained at the First Presbyterian Church in Casper. He was hired as chaplain at PGH and worked there from 1953 to 1957.

Selma_article_all2

In 1956 he discovered Unitarianism through reading Sophia Fahs’ book, Today’s Children and Yesterday’s Heritage. After exploring the Ethical Culture Society and Society of Friends, he decided he had found his spiritual home in the Unitarian Church. He resigned from his chaplaincy position at Philadelphia General Hospital July 1957 and became youth director of the Philadelphia West Branch YMCA where he worked until 1959. He became assistant, then associate, minister of All Souls’ Unitarian Church in Washington DC, where he worked until 1964 when he became Community Relations Director of the Boston Metropolitan Housing Program of the American Friends Service Committee.

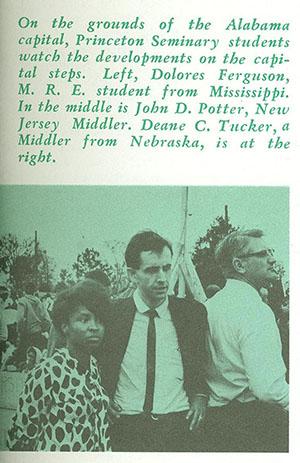

In March 1965, leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee organized peaceful demonstrations to bring national attention to the disenfranchisement of African American voters. Twenty members of the Princeton Seminary community joined the protest marches in Selma, Alabama. Participants included students, faculty and administration, all of whom were involved in every stage of the coordinated events. After police violently attacked demonstrators on March 7, students collected funds and formed a joint student-faculty “Ad Hoc Committee on Civil Rights” that kept the movement alive on campus.

Reeb saw the violence in Selma on television and responded to Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for clergy to join a second march two days later. After that march he and two other ministers who had participated ate dinner in an integrated restaurant nearby. When they left the restaurant they were attacked by four white men, one of whom hit Reeb on the head with a heavy club. He died two days later.

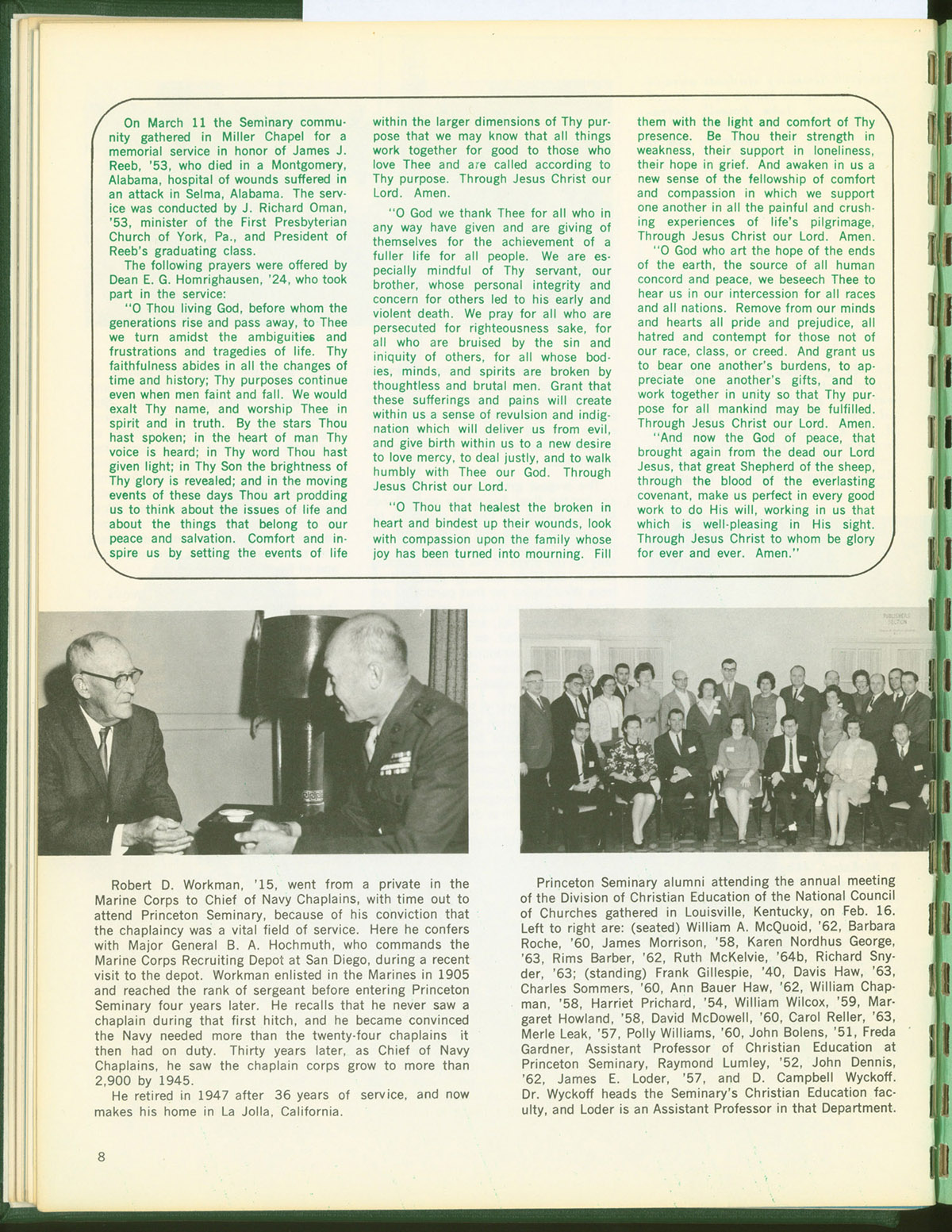

Seminary Dean and Professor of Christian Education E. G. Homrighausen led a memorial service for Reeb in Miller Chapel. In the Seminary Alumni News that spring President James I. McCord wrote:

“All of us are more deeply committed and more deeply involved because of the example of James Reeb, ’53, and the way he sealed his own dedication with his life. That human rights is the great moral issue of our time cannot be gainsaid, and all of us, faculty, students, and alumni, are challenged to bring the reconciling ministry of Jesus Christ to bear on this problem wherever it exists at home or abroad.”

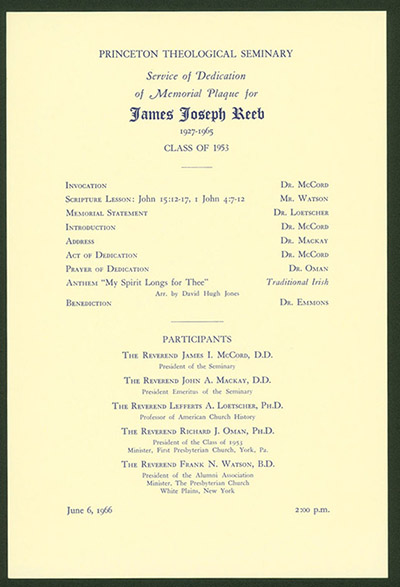

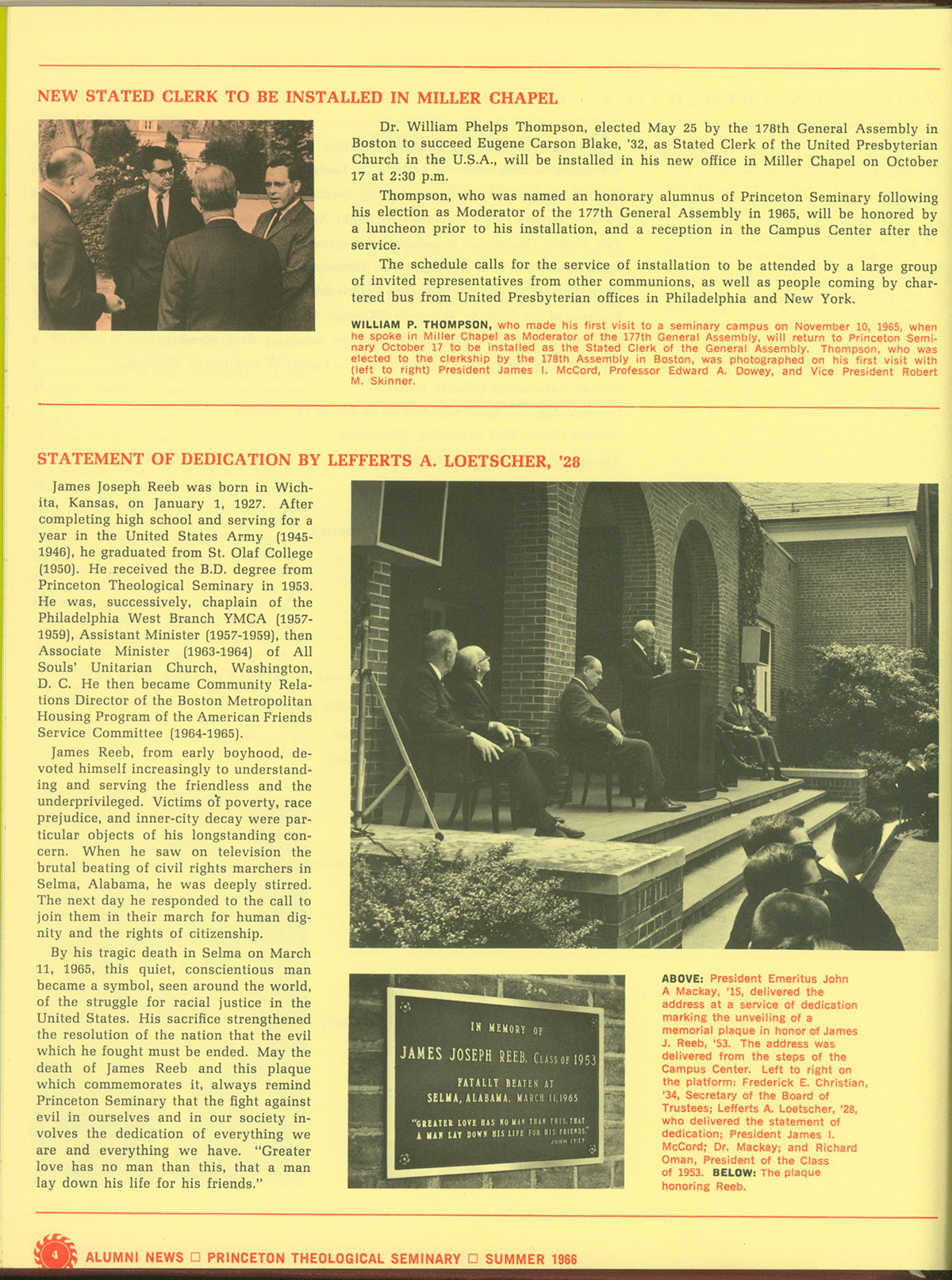

The Seminary Board of Trustees, in cooperation with the Alumni Council, then established the James J. Reeb Memorial Lectureship, with Eugene Carson Blake to deliver the first lecture. On Alumni Day, June 6, 1966, a plaque in Reeb’s memory was placed at the Mackay Campus Center during a dedication service on campus. Richard J. Oman, President of the Class of 1953, led a prayer of dedication. PTS Professor of American Church History Lefferts A. Loetscher gave a statement of dedication in which he said, “By his tragic death in Selma on March 11, 1965, this quiet, conscientious man became a symbol, seen around the world, of the struggle for racial justice in the United States.”

John A. Mackay, who was Seminary president when Reeb attended Princeton, also spoke at the dedication. James H. Moorhead wrote that Mackay “expressed both great admiration and a sad reservation about Reeb.” (Moorhead, 413)

Richard J. Oman returned to PTS in 1995 as Vice President for Academic Affairs at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary to preach at a service commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of Reeb’s death:

“How important it is that you and I reexamine the fundamental tenets of our faith on a continuing basis, for truth is never static. Jim Reeb believed this, and although his conclusions were not mine, I learned from his life the importance of the search. … Surely a second lesson to be gleaned from the James Reeb story is that the practice of ministry calls for decision.”